The Covid-19 pandemic incurred long-lasting effects, not just from death and disease directly caused by the virus, but also on Malaysians who got sicker over the past nearly two years.

Yet, the 12th Malaysia Plan (12MP), which outlines the government’s plans for the next five years from 2021 to 2025, barely acknowledges the massive toll of Covid-19 on the public health care system that was already underfunded and understaffed before the pandemic.

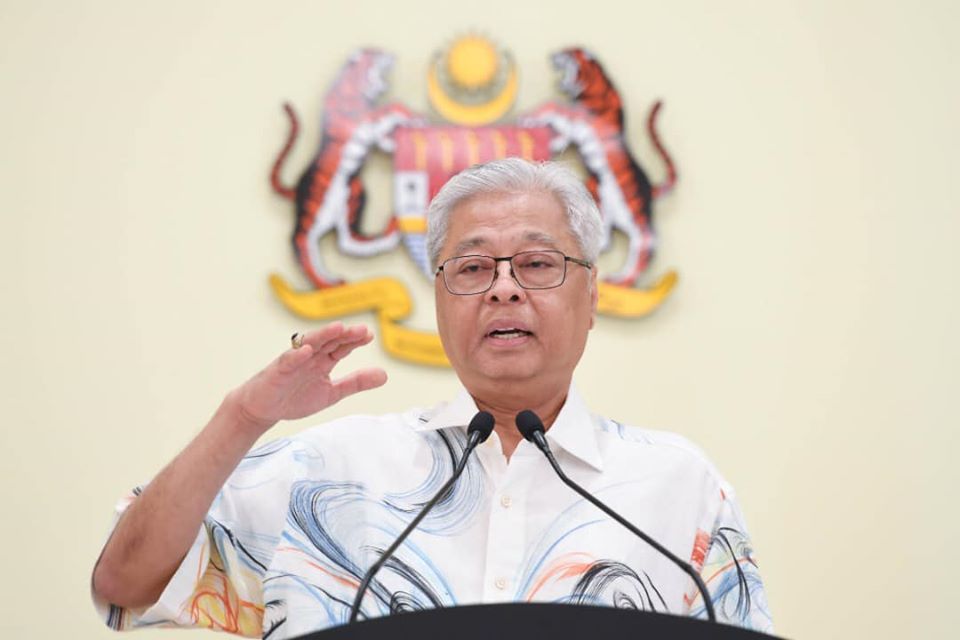

Instead, the 12MP — tabled by Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob in Parliament yesterday — suggests cosmetic improvements to health care service delivery as if Malaysia is picking up from where we left off at the end of 2019, before the coronavirus landed in our country in January last year.

The pandemic exposed deep gaps in the public health care system that was overwhelmed by waves of Covid-19 cases — to the point that Malaysia has the highest Covid-19 deaths per capita in the region — while non-Covid patients were neglected.

12MP fails to address the crucial points of public health, treatment for non-Covid patients who deteriorated during the pandemic, and human resource issues in the public health workforce.

No Pandemic Preparedness Playbook

Malaysia’s Covid-19 public health response arguably failed — according to some experts — as the virus overwhelmed testing, contact tracing, and health care capacity at numerous points of the epidemic.

Covid-19 highlighted the limits of Rt-PCR testing capacity that saw backlogs in rural states like Sabah, as well as the lack of genomic sequencing studies across the country. Only Sarawak has been able to sequence far more of its Covid-19 cases for variants compared to other states, thanks to University Malaysia Sarawak.

Yet, the 12MP omits crucial reforms of public health functions to prepare for the next pandemic. On Malaysia’s preparedness for health crises, the 12MP merely mentions increasing multi-hazard public emergency response teams at the country’s entry points, particularly the Kuala Lumpur International Airport, besides increasing awareness and mitigation programmes on various communicable diseases.

Ismail Sabri also proposed setting up a new centre for infectious diseases in Negeri Sembilan, even though there is already an existing Institute for Public Health (IKU), one of the research institutes by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the Ministry of Health (MOH). MOH’s Institute for Medical Research (IMR) also has an Infectious Disease Research Centre.

The millions spent on a new building could go toward research grants for IKU and IMR instead.

Absent Non-Covid Treatment

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, cancer was mostly detected late in Malaysian patients, rising to about 64 per cent in the 2012-2016 period from 59 per cent in 2007-2011. Cancer deaths rose nearly 30 per cent in that period.

Anecdotally, oncologists find an increased number of cancer patients presenting with advanced disease compared to pre-Covid times. Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin said last week that MOH hospitals have over 57,000 backlogged non-Covid procedures, without elaborating how long it would take to clear the backlog.

It is unknown how many patients with chronic diseases — such as cancer, diabetes, or kidney disease — are now suffering complications or advanced illness, or even died due to deferred treatment and delayed screenings during the pandemic.

The 12MP focuses on increased awareness programmes and more mobile health clinics to provide cancer screening services. However, what is needed in the short and medium-term, ie: over the next five years, is expanded treatment for non-Covid patients to prevent mortality, as they now require more expensive and complex care because of their inability to access early treatment.

Of note is health care programmes for the elderly in the 12MP as Malaysia moves towards aged nation status in 2030, but the government’s plan does not mention expanding social care for senior citizens in the public sector. Affordable social care for the elderly beyond the hospital setting is sorely lacking as private aged care can be quite expensive.

Missed Opportunity For Health Care Financing

The government deserves some credit for broaching the tricky topic of health care financing. Over the past two decades, through at least six reports on Malaysia’s health care system, it is well known that our health care system is unsustainable and ill-suited for the challenges of the 21st century. Yet another blueprint for Malaysia Healthcare System Reform, as suggested by the 12MP, seems unnecessary.

The 12MP boldly states that charges for higher-income patients in the public sector will be raised, as subsidies for health care services will be determined through a means test.

While it is high time to review subsidies for public health care — up to 98 per cent currently — raising patient fees alone won’t earn the government substantial revenue. The 12MP also should have elaborated on the government’s justification to increase patient fees — especially in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic that sent over half a million middle class households into the B40 category — beyond the vague reason of “financial sustainability”.

When the United Kingdom decided to implement a new health and social care tax, Boris Johnson’s government provided estimates on how proceeds from the tax would cover non-Covid cases backlogged in the NHS as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

The 12MP does not propose the true “game-changer” of a national health care insurance scheme, but instead moots a national health endowment fund derived from waqf, the donation of assets from Muslims. It’s unclear just how big or sustainable this fund can be to cover increasing health care costs as more Malaysians, made poorer by the pandemic, switch from private to public care.

Contract Doctors’ Issues Unresolved

The 12MP sets a 1:400 doctor-to-population ratio target by 2025. This ratio improved marginally from 1:482 in 2019 to 1:450 in 2020.

A United Nations expert previously estimated in August 2019 that 70 per cent of specialists are concentrated in the private health care system that treats just 30 per cent of complicated cases. So, the government can’t solely focus on improving the national doctor-to-population ratio (which is also far bigger in Sabah and Sarawak).

Yet, despite multiple anecdotes from government doctors across the country, who described burnout and overwork in their never-ending battle against Covid-19, the 12MP fails to mention plans to increase human resources in the public health care system.

Long-standing issues of contract doctors, which require substantial financial investments by the government, are left unresolved in the 12MP that merely proposes an enhancement of the National Postgraduate Training Programme to increase the number of medical specialists.

Such a proposal focuses on permanent doctors, even as the government increasingly relies on contract workers that comprise more than 41 per cent of the medical workforce in the public sector.

Boo Su-Lyn is CodeBlue editor-in-chief. She is a libertarian, or classical liberal, who believes in minimal state intervention in the economy and socio-political issues.