Try asking your parents or grandparents where they got their pneumococcal, meningococcal, influenza, varicella or shingles vaccines. They would probably give you multiple answers ranging from their family doctor, their General Practitioner (GP), their Family Medicine Physician or their General Physician.

Very occasionally, it might be from their child’s pediatrician, but it would be highly unlikely that it will come from a nurse or doctor in a health clinic of the Ministry of Health (MOH).

This is because apart from tetanus shots for pregnancies, there are no other adult vaccines in the National Immunisation Programme (NIP). However there is a wealth of knowhow, skills, experience and wisdom in the management of adult vaccination in the private health care sector.

Therefore, it makes a lot of sense to engage all the private practitioners, private hospitals and the Association of Private Hospitals Malaysia (APHM) early in the Covid-19 vaccine rollout programme. And with the wide network of GP clinics throughout Malaysia, it would ensure that virtually all of the potential adult beneficiaries would be served.

The many years of health care services provided by the family doctor has built an enviable bond of trust which would serve well to enhance the uptake of the new Covid-19 vaccines by their clients.

The word of the family doctor is worth much more than the marketing campaign by the MOH and the Special Committee for Ensuring Access to Covid-19 Vaccine Supply (JKJAV), and would form a solid buttress against the fake news and conspiracy theories that are prevalent in social media.

With the low and slow supply of vaccines, there is all the more reason to empower the private health care sector to procure other Covid-19 vaccines to help ramp up the speed of the vaccine rollout.

Firstly, this involves the conditional registration of more vaccines by the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Authority (NPRA).

Since the MOH is compliant with the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO), they should heed the recommendations of the WHO which has authorised under emergency use the Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Covershield, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna and most recently the Sinopharm vaccines.

It is pertinent to note that the Sinovac vaccine which is conditionally registered with the NPRA has yet to be recognised by the WHO.

This is a critical step because the Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Sinovac vaccines in the JKJAV portfolio have reached their thresholds in terms of supplies, thus the delayed and restricted supplies.

Also, the private health care industry should not be competing with the MOH for the same set and quota of Covid-19 vaccines. Instead, the MOH should disclose the variety of vaccines, with its multiple modus operandi, to the private health care industry for them to procure.

With the years of adult vaccine experience under their belts, they would be more than prepared to preserve cold chains, store and administer the vaccines. This would be relatively easier since the other mRNA vaccine, Moderna, does not require severe arctic temperatures for storage, unlike the Pfizer vaccine and the others can be stored in the temperatures provided by regular refrigerators.

Private health care practitioners would better serve their regular patients who frequent their practices, who otherwise would be at the bottom rung of the MOH vaccine rollout priority.

These include the expatriates, those who have insurance policies, the T20, the young businessman who needs to travel to rejuvenate his enterprise, the undergraduate or postgraduate student who needs to fly oversea to continue their studies, the migrant workers and the refugees.

The vaccines used will be above and beyond the vaccine stockpile of the JKJAV. With the movement of adults from the public to the private vaccine programme, more space will be created and those at the bottom half of the vaccine hierarchy would advance faster and get an earlier date for their shots.

The fears of creating inequities in vaccine distribution is unfounded. If anything, the equity of the vaccine programme would be better protected because young Muslim pilgrims planning to perform the hajj do not need to jump the queue and push back 30,000 more deserving and high-risk adults. They should and can rightfully pay for the Covid-19 vaccines at the private facilities.

Migrant workers and refugees who would bear the brunt of inequitable access to vaccines can now be afforded similar opportunities by their employers and the state government to prevent potential Covid-19 transmission to the wider community.

This programme would also allow vaccinees to pick their vaccines of choice. Some would prefer the classical inactivated vaccines (Sinopharm, Sinovac) which is associated with relatively lesser Adverse Effects Following Immunizations (AEFI).

Other well-read clients may prefer the latest mRNA technology vaccines (Moderna, Pfizer) which has the widest research base in clinical trials and real-world experience. Others may just want to enjoy the single-shot Johnson & Johnson and CanSinoBio vaccine.

There have been days when health care workers at vaccination centres were left idle because there were no vaccines available to be administered. In one incident, many elderly people were left in the lurch when a vaccine centre was closed.

On days when they had vaccines it was efficiently completed within the first half of the day. There exists the capacity and efficiency to administer two to three times the vaccines doses per day.

Now imagine if private hospitals were able to procure vaccines, they would be able to complement the limited supplies from the MOH with their own vaccine supplies and thus help to scale up the immunisation coverage.

The stringent centralisation of the Covid-19 vaccine programme by the present team with no prior or proven track record of adult vaccination, has proven to be a folly.

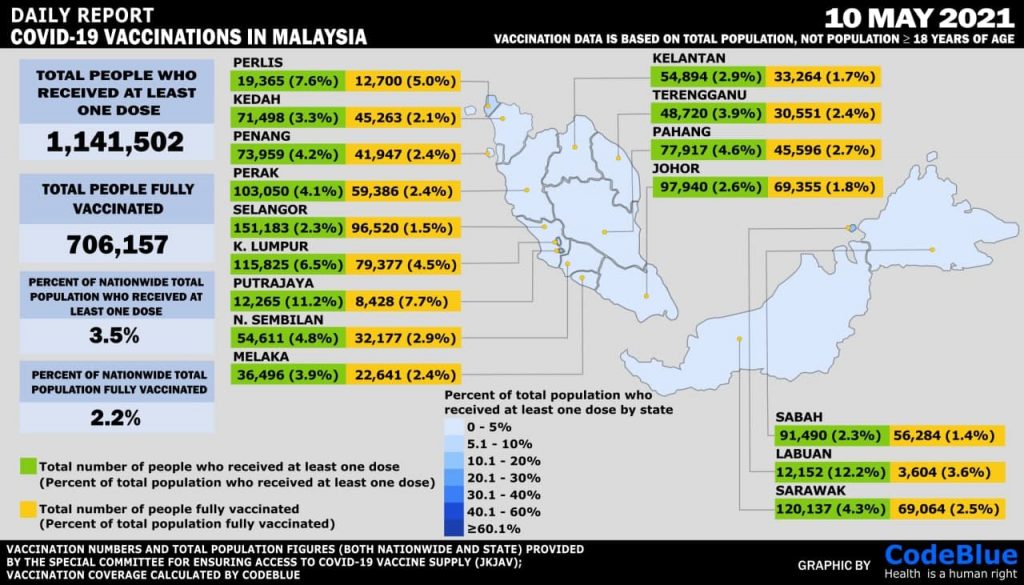

Since its launch in February 2021, we have only been able to immunise less than 4 per cent of our population. Worse still, the trajectory of the vaccine rollout is relatively flat.

The authorities insist that the vaccine shortage is beyond their control due to global competition and parochial nationalism. They also insist that everything related to the Covid-19 vaccines must be negotiated by the Federal Government.

This can no longer be sustainable because governments should only be the policymakers, and not play the role of implementers. Never before has the private health care sector been blocked from directly procuring any set or volume of vaccines.

When we speak about the equity of vaccine distribution, this function has now been completed, as we have “successfully” conducted Phase One, Phase One+ and Phase Two-A of the National Covid-19 Immunisation programme (PICK)

We are now at a stage where the goal is to immunise as many people as quickly as possible. If a segment of the population is able to pay for the vaccines, is this not something that the authorities should welcome to offset the national financial impact?

After all, the Prime Minister and the Finance Minister have used the financial crisis as justification for them to tap into our national savings. Surely industries and members of the public who are willing and able to pay for the vaccines should be able to access it.

Furthermore, by allowing segments of the population to purchase the vaccines (while not compromising the PICK supply) will ensure that we achieve herd immunity faster. Should that not be our ultimate goal?

Many of the ideas that have been articulated are not complicated, but are actually run-of-the-mill, best vaccination practices. A smart partnership between the public and private health care sectors is vital to ensure a warp speed vaccine rollout, scale up coverage of the population, and preserve equitable distribution of the Covid-19 vaccines.

When the Indian government began their vaccine rollout, it was able to administer 300,000 doses per day. With the active participation of the private health care sector, they were able to increase it by seven times to two million doses daily.

We can achieve something similar, if not better, with the willingness shown by the APHM, GPs, private hospitals and the state governments (notably Selangor with its 6.9 million residents, contributing 25 per cent of the country’s GDP) to immunise more Malaysians, and the public enthusiasm for the opt-in AstraZeneca vaccine programme.

This would undoubtedly complement and enhance the drive towards achieving population immunity.

In conclusion, the following caption from a twitter feed best illustrates the present state of affairs. It is an indictment of the present Covid-19 vaccine rollout programme, and must be addressed urgently: “There is a large fire in our house and we’ve decided to put it out by bringing water from a well outside of our house by using tiny, tiny cups”.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.