KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 13 — A 38-year-old Sarawakian man died after Lawas district hospital, lacking a trauma specialist, transferred him to Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, three hours away to treat injuries from an accident.

Sarawakian rural health activist Agnes Padan said Suhandi Timbang, a local fisherman from Kampung Awat-Awat near the Brunei border, came to Lawas hospital last month to seek treatment for his broken bones after he got into a motorbike accident. The district hospital is about 1,000km away from Kuching.

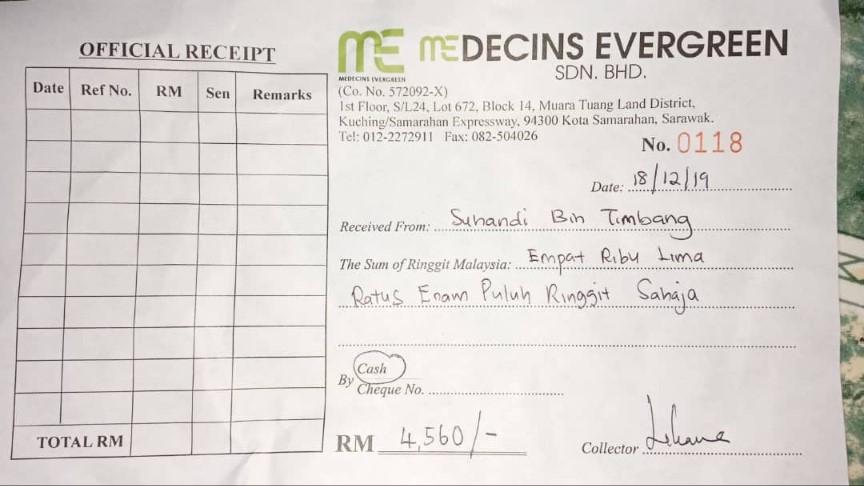

Suhandi was admitted to the Lawas hospital on December 14 at around 7pm, but was moved to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital 1 (QEH1) in Kota Kinabalu 180km away at midnight that same day because it was the nearest government hospital with a trauma specialist. He received surgery at QEH1 only three days later, as his family had to raise funds to cover the purported RM4,500 operation at the public hospital.

Suhandi, unfortunately, died on December 20 due to acute respiratory distress syndrome, a condition that is typically triggered by a previous health problem, including injuries from a traffic accident.

Agnes, whose mother Kam Agong died in 2002 following maternal complications at the Lawas hospital, said cases of patients at the public hospital being rerouted elsewhere were the norm. This, she said, is unfortunate as not many in Sarawak can afford to travel to other hospitals.

“He was not attended by a doctor immediately, and had to wait more than 30 minutes,” Agnes alleged, referring to Suhandi.

“After they had an X-ray carried out, they decided to transfer him to QEH1 hospital in an ambulance free-of-charge. But the fact he survived for five days after the incident means he could have been saved,” she told CodeBlue.

“A young guy shouldn’t die from broken bones. He should not have been made to travel 200km.”

Agnes Padan, Sarawak rural health activist

Agnes also questioned the hefty fees that she claimed Suhandi’s family was forced to cough up before the surgery could be performed at QEH1, noting that his family was a low-income household.

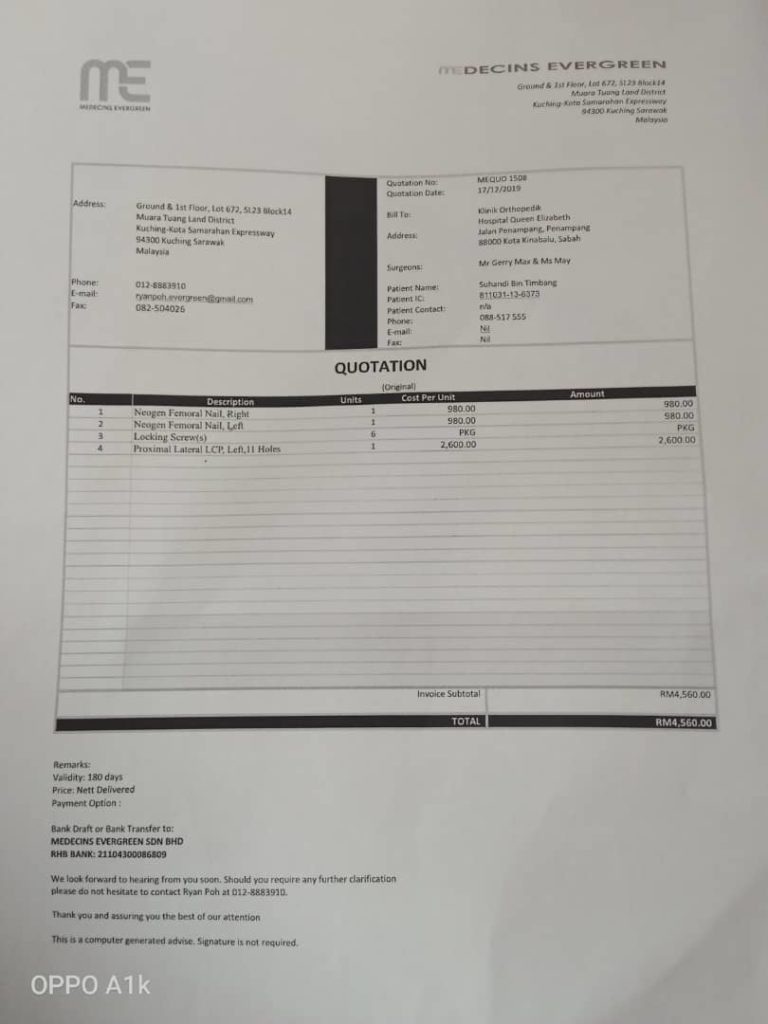

According to Agnes, the RM4,560 surgery fee included the cost of procuring two femoral nails and a proximal lateral locking compression plate, which went to Medecins Evergreen Sdn Bhd, the vendor that provided the orthopaedic implants, not the hospital, according to a friend of hers who worked at QEH1.

Agnes said she has been in touch with Suhandi’s sister, who alleged that staff from QEH1 threatened to delay the surgery or not do it at all until payment was made.

Suhandi was not insured, and no reason was given by the hospital as to why the surgery was so expensive. QEH1 is a government hospital, and the family expected treatment there to not burn a hole through their pockets.

Suhandi’s sister eventually collected funds from her friends and family members, and the surgery was carried out one day after she paid for it.

However, after Suhandi’s 12-hour operation, he succumbed to his injuries when he was in the intensive care unit of QEH1. He was laid to rest in his village last month.

When contacted, a QEH1 spokesperson said the hospital is probing the matter.

“HQE will conduct an investigation of the feedback provided, and will notify you as soon as the investigation is complete,” QEH1 corporate communications head Sulia Banying Anak Gihang told CodeBlue.

Meanwhile, a spokesman for Medecins Evergreen, the vendor which provided the orthopaedic implants for QEH1, confirmed that the quotation and receipt they issued for the hospital was valid, and denied that his company threatened the patient’s family.

The spokesman, who declined to be named, said his group’s standard procedure is to provide partner hospitals with fee quotations for medical implants. The company doesn’t directly deal with patients or know their backgrounds, like if the patient is from the bottom 40 per cent (B40) or not.

“We do not call the patients and we are not given any information about patients’ background as well. All this information we don’t have. We are basically a supplier of implants to the hospitals for patients. These implants are not available in hospitals; therefore, the hospital requests us to provide them a quotation,” the Medecins Evergreen spokesman told CodeBlue.

“So, we will quote according to what is requested by the doctors, then we email this to the doctors who are in charge for all this, and then the doctors will pass the quotation to the patient. That is the normal procedure.

“We do not call patients directly to so-called…force the patient to pay a hefty…payment. We do not contact the patients. We only provide quotations requested by the hospitals.”

Agnes said most of the cases presented to the Lawas hospital seem to be trauma, orthopaedics and infections, so having a trauma specialist there should not be too much of an ask.

Trauma and orthopaedics are not “rocket science” either, and it would not be difficult to train specialists in this field, she said.

“We need a full emergency trauma team, including specialists who can carry out surgery, orthopaedics, and obstetricians and gynecologists,” she said. “Otherwise, these patients still risk a three-hour journey to Kota Kinabalu, or a five-hour journey to Miri.”

The Ministry of Health did not immediately respond when asked for comments.

Agnes, meanwhile, called for a proper radiology unit with a CT scanner and an MRI machine — not just an X-ray — to be included at the new Lawas Hospital, the groundbreaking ceremony of which was held a little over three weeks ago.

The RM175 million project, set to be completed in 2023, will replace the existing 50-year-old non-specialist Lawas hospital, which only has 46 beds. It is expected to have 76 beds, a hemodialysis unit, a maternity room, mortuary, blood bank, and an X-ray room.

The existing Lawas hospital caters to over 35,000 villagers from as far as Ba’kelalan near the Indonesian border, where Agnes hails from. Patients who require specialists are referred to other government hospitals in the state and in nearby Sabah.

Agnes said every district general hospital in Sarawak should have a CT scanner, an emergency trauma team, and an obstetrics and gynaecological team, given the distance that patients have to travel to get medical treatment in the state.

“Sometimes, patients with complicated cases need to be transferred to a bigger centre, but at least the initial stabilisation and optimisation of critically ill patients can be done at the district hospital level,” she said, lamenting that this could not be done for Suhandi.