KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 10 — General practitioners (GPs) in Malaysia are not equipped or incentivised to care for patients with chronic illnesses despite an epidemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), an expert said.

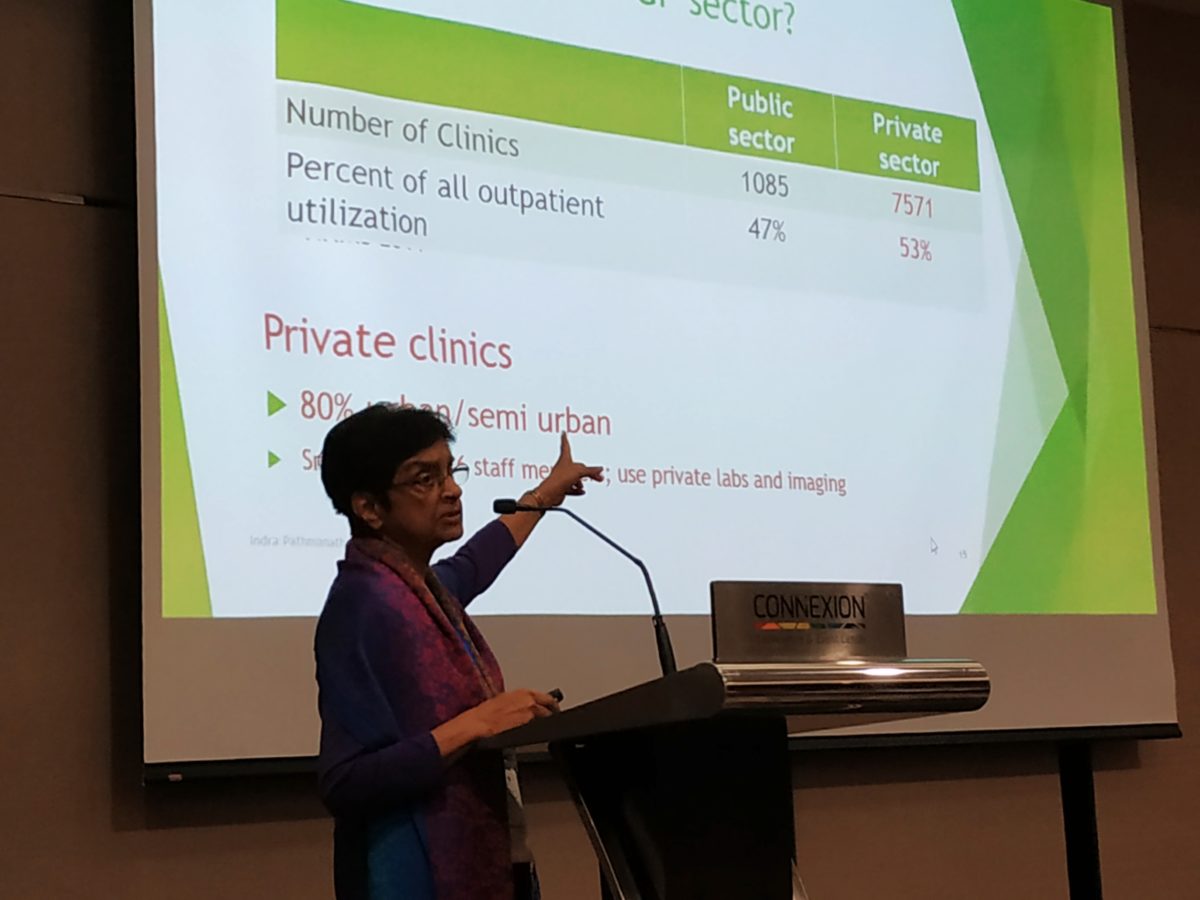

Dr Indra Pathmanathan, a senior public health consultant at United Nations University’s International Institute for Global Health, said the 7,500 GP clinics in the private sector, most of which have less than six staff, see over half of Malaysia’s primary care patients.

But she pointed out that private family doctors generally treated patients with acute episodes of illness, while public health clinics provided long-term care for people with NCDs like diabetes or high blood pressure.

“We already know we’re having an epidemic of NCDs which require long-term care. GPs are not responding to that,” Dr Indra told the Second Federation of Private Medical Practitioners’ Association, Malaysia (FPMPAM) Malaysian Health Care Conference here recently.

According to the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015, 17.5 per cent of the adult population in Malaysia aged 18 and above (3.5 million adults) suffered from diabetes, while 30.3 per cent of adults (6.1 million people) had hypertension, or high blood pressure. About 9.6 million people in Malaysia, or 47.7 per cent of the adult population, had high cholesterol.

Dr Indra said clinic GPs’ consultation fee was too low, pointing out that the family doctors were not compensated for the amount of time they advised patients on how to prevent or manage their diabetes or hypertension, as doctors only charged for medicine.

Clinic GPs have long complained about their consultation fees that have been capped by the government at RM10 to RM35 since 1992. Pakatan Harapan is still deciding on whether or not to raise their rates to RM30 to RM125, as charged by hospital-based GPs.

The out-of-pocket payment system for private clinics doesn’t encourage patients to stick to the same doctor either, Dr Indra said, as she highlighted doctor-hopping in instances when physicians refuse to give patients antibiotics.

She said insurance schemes and managed care organisations (MCOs), which offer managed health care plans by contracting with insurers or employers, also discourage GPs from providing long-term and preventive care.

Australia and Singapore, Dr Indra said, give GPs bonus payments based on the number of patients they follow up with and the percentage of patients whose illness like diabetes or high blood pressure is under control. But Malaysia has no such incentives for GPs to upgrade their practice with computer systems that enable follow-ups with patients.

“In order to do proper long-term care, you need to have information systems that allow you to do follow-up and recall patients who have not come for their follow-up and so on,” she said.

“The systems are not in favor of the GPs providing the type of care which is likely to have a rising demand in future.”

Dr Indra Pathmanathan, senior public health consultant

“In other words, we can have more doctors coming in, but they’re all trying to compete for a limited number of patients with acute illness.”

Malaysian GPs also aren’t given vocational training before they practice as family physicians, unlike in the United Kingdom that requires three to four years of training to be a GP after graduating from medical school.

“We don’t have such requirements. So, the content of whatever the GPs are trained to do is not truly linked to enable them to manage the more complex kind of conditions that are likely to be the morbidity pattern of the country,” Dr Indra said.

Malaysia’s payment system for GPs doesn’t incentivise group practices, where other health care workers like nurses can save doctors’ time by performing screenings.

Malaysian GPs also have to compete with government clinics like Klinik Komuniti (previously 1Malaysia clinics), private specialists who provide primary care, and pharmacies that sell the medicines which are also sold by family physicians to keep their business afloat amid low consultation fees.

“So actually, the GP sector is under threat from so many different angles,” Dr Indra said.

She questioned why the government can’t cover payments for GPs, even though the Health Ministry claims that its allocations under the national budget are very restricted.

“My question is — is it because we don’t have enough money, or is it because we don’t have political commitment to get that money?

“We seem to have political commitment to get money for all kinds of things, but definitely not to pay GPs more or make sure GPs can be financially viable in order to provide the kind of care the country is going to need.”